|

|

|

joune. 22. 201`0 |

The Red Snake: The Great Wall of Gorgan

The Great Wall of China is well known as the largest wall in Asia (or indeed the world). Less known is the Wall of Gorgan in northeastern Iran (specifically the plain of Gorgan) attributed to the Sassanian era (224-651 AD). The structure is yet another testament to Sassanian engineering capabilities.

According to the Science Daily News (February 26, 2008) the Wall of Gorgan is:

“…more than 1000 years older than the Great Wall of China, and longer than Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall put together.”

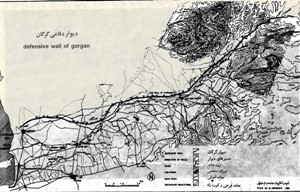

The ‘Red Snake’ in northern Iran, which owes its name to the red colour of its bricks, is at least 195km long. A canal, 5m deep or more, conducted water along most of the Wall. Its continuous gradient, designed to ensure regular water flow, bears witness to the skills of the land-surveyors responsible for marking out the Wall's route. Over 30 forts are lined up along this massive structure. It is also known as the Great Wall of Gorgan, the Gorgan Defence Wall, Anushirvân Barrier, Firuz Barrier and Qazal Al'an, and sometimes Sadd-i-Iskandar, (Persian for dam or barrier of Alexander).

The wall is second only to the Great Wall of China as the longest defensive wall in existence, but it is perhaps even more solidly built than the early forms of the Great Wall. Larger than Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall taken together, it has been called the greatest monument of its kind between Europe and China.

The 'Red Snake' is unmatched in so many respects and an enigma in yet more. Even its length is unclear: its western terminal was flooded by the rising waters of the Caspian Sea, while to the east it runs into the unexplored mountainous landscape of the Elburz Mountains. An Iranian team, under the direction of Jebrael Nokandeh, has been exploring this Great Wall since 1999. In 2005 it became a joint Iranian and British project.

The inhabitants of this region are generally believed to have been the ancient Hyrcanians. Gorgan itself is one of Iran’s most ancient regions and is situated just to the Caspian Sea’s southeast. Gorgan has been a part of the Median, Achaemenid (559-333 BC), Seleucid, Parthian (247 BC-224 AD) and Sassanian empires in the pre-Islamic era. The term Gorgan is derived from Old Iranian VARKANA (lit. The Land of the Wolf). Interesitngly the term Gorgan linguistically corresponds to modern Persian’s “Gorg-an” or “The Wolves”.

The capital of ancient Gorgan was known as Zadrakarta, which later became Astarabad. This city can be traced back to at least the Achaemenid era. Another historical city of importance was ancient Jorjan.

Until recently, nobody knew who had built the Wall. Theories ranged from Alexander the Great, in the 4th century BC, to the Persian king Khusrau I in the 6th century AD. Most scholars favoured a 2nd or 1st century BC construction. Scientific dating has now shown that the Wall was built in the 5th, or possibly, 6th century AD, by the Sasanian Persians. This Persian dynasty has created one of the most powerful empires in the ancient world, centred on Iran, and stretching from modern Iraq to southern Russia, Central Asia and Pakistan.

With the benefit of hindsight it is easy to see why the walls would have been constructed at this later date. It was near the northern boundary of one of the most powerful empires in the ancient world, that of the Sasanian Persians. Centred in modern Iran, it also encompassed the territory of modern Iraq, stretched into the Caucasus Mountains in the north-west and into central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent in the east. The Persian kings repeatedly invaded the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. Yet, they also faced fierce enemies at their northern frontier. Mountain passes in the Caucasus and the coastal route along the Caspian Sea were closed off by walls, probably to prevent the Huns from penetrating south. Ancient writers, notably Procopius, provide graphic descriptions of the wars Persia fought in the 5th and 6th century against its northern opponents. The Persian king Peroz (AD 459-484), when campaigning against the White Huns, spent time repeatedly at ancient Gorgan. Eventually he had to pay with his life for venturing into the lands of the White Huns. It would have made perfect sense for Peroz, or perhaps another Persian king shortly before or after, to protect the fertile and rich Gorgan Plain from this northerly threat through a defensive barrier.

Modern survey techniques and satellite images have revealed that the forts were densely occupied with military style barrack blocks. Numerous finds discovered during the latest excavations indicate that the frontier bustled with life. Researchers estimate that some 30,000 soldiers could have been stationed at this Wall alone. It is thought that the 'Red Snake' was a defence system against the White Huns, who lived in Central Asia.

The system of castles was developed by the Sassanians into a system of fluid defense. This meant that the Gorgan Wall was not part of a purely static system of defense. The main emphasis was in a system of fluid defense-attack system. This entailed holding off potential invaders along the line and in the event of a breakthrough, the Sassanian high command would first observe the strength and direction of the invading forces. Then the elite Sassanian cavalry (the Savaran) would be deployed out of the castles closest to the invading force. The invaders would then be trapped behind Iranian lines with the Gorgan Wall to their north and the Savaran attacking at their van and flanks. It was essentially this system of defense that allowed Sassanian Persia to defeat the menacing Hun-Hephthalite invasions of the 6-7th centuries AD.

Radiocarbon dates indicate that the fort remained occupied until at least the first half of the 7th century. It is too early to tell whether or not the Wall was abandoned then, perhaps because troops were needed for a major assault against the Byzantine Empire, fighting off the Byzantine counter-offensive or against the Arab invasion from AD 636 onwards. The evidence is mounting, however, that the Wall functioned as a military barrier for at least a century and probably closer to two.

If one assumed that the forts were occupied as densely as those on Hadrian's Wall, then the garrison on the Gorgan Wall would have been in the order of 30,000 men. Models, taking into account the size and room number of the barrack blocks in the Gorgan Wall forts and likely occupation density, produce figures between 15,000 and 36,000 soldiers.

The land corridor between the Caucasus Mountains and the west coast of the Caspian Sea is closed off by a series of walls. The most famous is the Wall of Derbent in modern Dagestan (Russia). Then, much closer to the 'Red Snake' is the contemporary Wall of Tammishe, which runs from the south-east corner of the Caspian Sea into the Elburz Mountains. The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland sea and depends on inflowing rivers for its water. Its water level has thus fluctuated much more over the centuries than that of the oceans.

This wall starts from the Caspian coast, circles north of Gonbade Kavous, continues towards the northwest, and vanishes behind the Pishkamar Mountains. A logistical archaeological survey was conducted regarding the wall in 1999 due to problems in development projects, especially during construction of the Golestan Dam, which irrigates all the areas covered by the wall. At the point of the connection of the wall and the drainage canal from the dam, architects discovered the remains of the above wall. The 40 identified castles vary in dimension and shape but the majority are square fortresses, made of the same brickwork as the wall itself and at the same period. Due to many difficulties in development and agricultural projects, archaeologists have been assigned to mark the boundary of the historical find by laying cement blocks.

Attention must be likewise given to a similar Sassanian defence wall and fortification on the opposite side of the Caspian Sea at the port of Derbent and beyond. Where the Great Wall of Gorgan continues into the Sea at the Gulf of Gorgan, on the far side of the Caspian emerges from the Sea the great wall of Caucasus at Derbent, complete with its extraordinarily well preserved Sassanian fort.

While the fortification and walls on the east side of the Caspian Sea remained unknown to the Graeco-Roman historians, the western half of this impressive "northern fortifications" in the Caucasus were well known to Classical authors.

This project is seriously challenging the traditional Euro-centric world view. At the time when the Western Roman Empire is collapsing and even the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire under great external pressure, the Sasanian Persian Empire musters the manpower to build and garrison a monument of greater scale than anything comparable in the west. The Persians seem to match, or more than match, their Late Roman rivals in army strength, organizational skills, engineering and water management. Archaeology is beginning to paint a clearer picture of an ancient super power at its apogee.

http://www.iranreview.org/content/view/5773/51/

کميته بين المللی نجات پاسارگاد